Politics of silence

MO.CO. graduate exhibition Esba 2021

Guest curator: Aliocha Imhoff

With Guillaume BOILLEY / Mathilde CORBI / Kim DEPARTE / Flavien DESRAY / Galliane DIDIER / Lisa EMMANUELIDIS / Celia FAVARETTO / Diane GROSBOIS / Anaëlle GUILLERMONT-CANALE / Marine HAMON / Judith HASSINE / Noemi LANCELOT / Chia LEE / Rosalie MOREAU / Ema OLTRA-JANDRIEU / Matthieu RAMON / Madeleine TAIT-JAMIESON / Laura VIALLA / Lingjun YUE / Yang YUE

From the ineluctable equation silence = death to the silence breakers of recent movements, enunciative politics has taught us to be wary about silence, and to always seek to break it. But when it is not confused with absence, silence can sometimes constitute powerful strategies of resistance, from a way of making ourselves ungovernable to a way of making the silence that now constitutes us as subjects of the Anthropocene resonate differently.

Location: École Supérieure des Beaux Arts Montpellier Contemporain / 130 Rue Yéhudi Ménuhin, 34000 Montpellier

From June 26 to July 11, 2021

Opening June 25, 4pm to 9pm.

Politics of silence

[Silence] is a presence

it has a history a form

Do not confuse it

with any kind of absence

Adrienne Rich, Cartographies of Silence, 19781

Breaking the silence

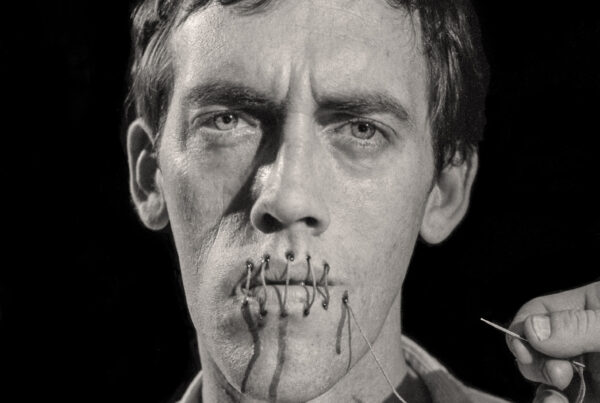

When silence persists as a symptom of being silenced, nothing should remain under silence, like the silence breakers of the #MeToo movement. By critiquing silence, silenced people reveal the structures and describe the processes by which silence is produced. It’s not just the content, but also the mechanisms for regulating speech, the rules and models of discourse that need to be questioned, those by which various circles of silence are formed and re-formed, from the impossibility of saying to the silent complicity of those who know.

Silence thus appears, first and foremost, as a form of oppression, erasure and annihilation, while we should pursue our efforts to celebrate the spoken word, the ways of accessing enunciation. We would thus be following in the footsteps of radical feminists of color like Audre Lorde, who taught us that silence “will not protect [us]”2 and that “silence has never given us anything worthwhile”3 or Cherríe Moraga, who wrote that “silence is like famine”4. We would follow those who asked us to break the silence, those who made coming out the privileged means of access to social legitimacy against the epistemologies of the closet5 that shaped hidden public lives. We’d be following the Act-Up activists’ inescapable equation: silence = death.

This articulation between silence and powerlessness presupposes a political imperative: that transforming the conditions of one’s oppression requires (re)finding one’s voice.

Democratic pharmakon

Speaking out, its unfailing celebration, appears at the same time as a democratic pharmakon6, both as a remedy and as a poison, in that access to speech constitutes the fundamental requirement of democracy – what Hannah Arendt called a “right to the right” – while being inscribed in asymmetrical power relations. Political representation – that is, the possibility of constituting a unified voice, one that is politically audible and heard – is the primary site of this profound ambivalence, since representatives, by speaking “in the place of”, redouble the silence of the represented. This ambivalence is compounded by a second, in that representation constructs the very norm of the representable, so that the audibility of speech expressed in the public sphere depends on the degree of conformity to it. Silence can therefore be understood as a strategy of resistance, a way of resisting the process by which governmentality emerges: a way of making oneself ungovernable.

Silent resistance

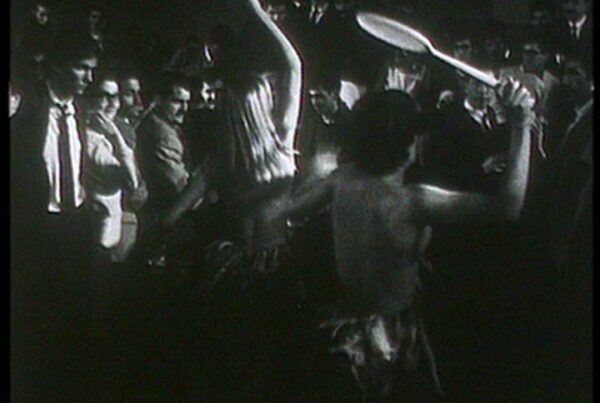

In 2013, feminist theorists Sheena Malhotra and Aimee Carillo Rowe published a remarkable anthology entitled Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at the Edges of Sound7 in which they set out to challenge the binaristic relationship that has been attributed since antiquity to voice vis-à-vis silence, so as to provide “a new imaginary of how the spaces between silence and voice might be traversed” (ib.). The authors of this book thus mobilize the legacies that have made silence the site of agentivity and a site of resistance, from the Buddhism of Thich Nhat Hanh, who wrote that “silence comes from our heart, not from the absence of speech” (ib. 3) to the work of Keith Basso, who in the 1970s laid the foundations for the theorization of silence, voice and culture in the field of anthropology8 or the filmmaker and poet Trinh T. Minh-Ha, who in 1989 drew our attention to “the suspension of language” as a prerequisite for getting to know the other, and wrote that “silence as a will not to say and as its own language has scarcely been explored.”9. They write: “Like the spaces between steps, or the breath within the breath, there is a kind of deep and abiding knowledge that comes from the spaces between words, the spaces between silences.”10.

As Sheena Malhotra again writes, “words fill the Western canon, speech is valued: take a stand; speak, speak, speak!”. If the fear of not being heard, of being invisible, is a valid fear, there is also an injunction to speak out. Silence can become a space of resistance, as long as it distinguishes itself from imposed silences, and is not confused with absence, as the poet Adrienne Rich wrote in 1978, “Do not confuse it / With any kind of absence”.

Every year, GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network) organizes a Day of Silence11 in the USA. All participants remain silent to protest discrimination against sexual minorities. This demonstration replaces a forced silence with a chosen commemorative silence, making silence a visible physicality. In this way, silence is not the opposite of speech, but rather a different form of discourse, with its own modes of intelligibility and grammar. Silence, like the zero in mathematics, is always a function.

Politics of nature, politics of silence

Today, silence has reached a new stage. In the Anthropocene era, the silent voice of the world is catching up with us, so much so that we need to relearn how to listen to those who literally don’t speak, or rather, those who “conjugate verbs in silence”12 as the poet Jean-Christophe Bailly wrote. So we should finally be silent to hear what the world itself has to say. Should we consider the noisy silence of the world as a missing figure whose continual search for a voice is now politically necessary? Should we now learn to translate silences and listen to the unspoken? The literary Marielle Macé recently postulated that speech being “one of the most polluted regions on the planet”13Marielle Macé, “Parole et pollution”, AOC media – Analyse Opinion Critique, January 28, 2021, https://aoc.media/opinion/2021/01/28/parole-et-pollution/. 14, only poets, since their audacity in inventing phonatory, syntactic and enunciative apparatuses, are in a position to welcome new voices, or rather “voices without voices, words without words, confronting the enigma that there is, in fact, in speaking” (ib.).

Silence becomes a doubly paradoxical power. Silence is at once the impossible voice of birds as political expression, the very untranslatability of their voice in democratic space, as well as that of our collective mourning in the face of agrarian depopulation, the heavy silence of this absence already there and yet to come.

Now, if it is silence – this double silence – that constitutes us as subjects of the Anthropocene, then we need to build a politics of silence in the years to come. A politics of silence that would undoubtedly consist in refusing to remain silent in the face of the urgent need to be silent as a means of putting an end to the world’s apparent silence.

Aliocha Imhoff

February 2021

Thanks : Nicolas BOURRIAUD, Yann MAZEAS, Marjolaine CALIPEL, Laëtitia DELAFONTAINE, Grégory NIEL, l’équipe technique et administrative de l’ESBA, MOCO.

Footnotes

- Traduit en français, Marie-Christine Lemardeley-Cunci, Adrienne Rich : Cartographies du silence, Lyon, Presses Universitaires de Lyon, 1990.

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches.., Reprint, Berkeley, Calif, Crossing Press, 2007

- Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals, Penguin, 2020, p. 10.

- Cherrie Moraga, “La Guera”, in: G. Anzaldua. C. Moraga. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, 2nd edition, New York, Kitchen Table Press, 1983

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, translated by M. Cervulle, Paris, Amsterdam, 2008.

- Pauline Julien, “Faire parler pour faire taire : les silences du consensus”, paper for the interdisciplinary colloquium Faire silence. Expériences, matérialités et pouvoirs, Marseille, May 21-25, 2019, https://fairesilence.sciencesconf.org/271723.

- Sheena Malhotra and Aimee Carillo Rowe, Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at the Edges of Sound, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Keith H. Basso, “To Give up on Words”: Silence in Western Apache Culture”, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 1970, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 213-230

- Trinh T. Minh-Ha, “Not You. Minh-Ha, “Not You/Like You: Post-Colonial Women and the Interlocking Questions of Identity and Difference”, in: G. Anzaldua (ed.), Making Face, Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color, San Francisco, Calif., Aunt Lute Books, 1990

- Sheena Malhotra and Aimee Carillo Rowe, Silence, Feminism, Power, op. cit. p. 14.

- https://www.glsen.org/day-of-silence

- Jean-Christophe Bailly, Le parti pris des animaux, Paris, Christian Bourgois, 2013