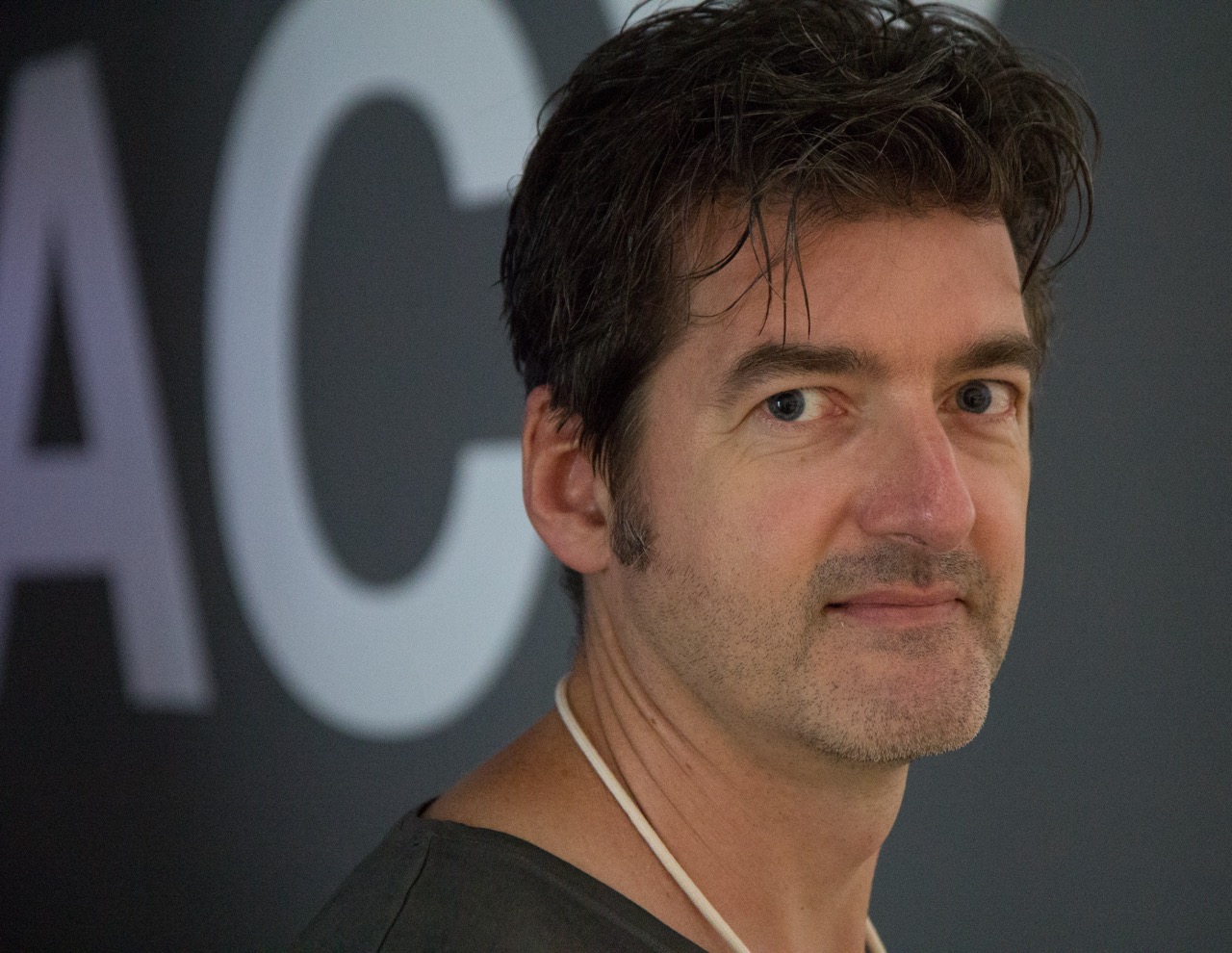

Oliver Ressler

Oliver Ressler, artiste et commissaire d’exposition, vit et travaille à Vienne. Son travail, composé d’installations dans l’espace public et de vidéos interroge le capitalisme global, les formes de résistances, les alternatives sociales, le racisme, la génétique. Il a participé à plus de 150 expositions, dont la biennale de Prague (2005), de Séville (2006), Moscou (2007) et de Taipei (2008). A la biennale 2008 de Taipei (Taiwan), il était également commissaire d’une exposition sur le mouvement altermondialiste. Ses films ont été présentés dans de nombreux festivals de films, événements politiques, cinémas et parfois aussi à la télévision. En 2002, sa vidéo « This is what democracy looks like ! » gagnait le 1er prix de l’International Media Art Award of the ZKM.

This is what democracy looks like!

d’Oliver Ressler (2002, 38min)

The video “This is what democracy looks like!” thematizes the events of 1 July 2001 which took place surrounding a demonstration against the World Economic Forum – a private lobbying organization of major capital – which was meeting in Salzburg at the time.

“At those meetings, in the absence of the public, billion dollar deals are set into motion by the self-appointed ‘global leaders.’ These deals bring wealth and prosperity to a few, and exploitation and poverty to many. To assure the orderly proceedings of economic globalization, the conference facilities, located in the center of Salzburg, are largely blocked off and all demonstrations are forbidden other than a rally at the square in front of the train station.” (Excerpt from the introduction of the video)

This video gives insight into the course of events of the first “anti-globalization demonstration” in Austria, held subsequent to the demonstrations in Seattle, Prague, Davos, Quebec, and Gothenburg, which all received a great deal of media attention.

Disobbedienti

d’Oliver Ressler & Dario Azzellini (54min, 2002)

The video “Disobbedienti” thematizes the Disobbedienti’s origins, political bases, and forms of direct action on the basis of conversations with seven members of the movement.

The Disobbedienti emerged from the Tute Bianche during the demonstrations against the G8 summit in Genoa in July 2001. The “Tute Bianche” were the white-clad Italian activists who used their bodies – protected by foam rubber, tires, helmets, gas masks, and homemade shields – in direct acts and demonstrations as weapons of civil disobedience. The Tute Bianche first appeared in Italy in 1994 in the midst of a social setting in which the “mass laborer,” who had played a central role in the 1970s in production and in labor struggles, was gradually replaced in the transition to precarious post-Fordist means of production. By forcing the closing of detention camps through specially developed acts of dismantling the Tute Bianche became involved in protests against precarious working conditions and the immigrants’ struggle for freedom of movement. The Tute Bianche were part of the demonstration against the WTO in Seattle in 1999 and the IMF in Prague in 2000. They sent delegates to the Lakandon rainforest in Chiapas and accompanied the Zapatist Comandantes 3,000 kilometers to Mexico City.

At the G8 summit in Genoa the Tute Bianche decided to take off their trademark white overalls that had given them their name and instead blend in the multitude of 300,000 demonstration participants. The transition from the Tute Bianche to the Disobbedienti, the disobedients, also marked a development from “civil disobedience” to “social disobedience.” The repressive actions and massacre by the police force in Genoa brought the practice of social disobedience in from the streets to the most diverse social realms. In the video, the Disobbedienti spokesperson Luca Casarini describes the Tute Bianche as a subjective experience and a small army, whereas Disobbedienti is a multitude and a movement.

Disobbedienti maintains the political form of the Tute Bianche and attempts to create a better legal justice for and from the people. Spectacular actions are still being carried out against detention centers, such as the dismantling of the detention camp in the Via Mattei in Bologna on 25 January 2002, as shown in the video. Additionally, attempts are being made to further develop “social disobedience” as a collective practice of various groups, to block the flows of goods and communication, to make general the strikes of individual groups, and to plan and carry out general strikes.

What Would It Mean To Win?

d’Oliver Ressler et Zanny Begg (40min, 2008)

“What Would It Mean To Win?” was filmed on the blockades at the G8 summit in Heiligendamm, Germany in June 2007. In their first collaborative film Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler focus on the current state of the counter-globalisation movement in a project which grows out of both artists’ preoccupation with globalisation and its discontents. The film, which combines documentary footage, interviews, and animation sequences, is structured around three questions pertinent to the movement: Who are we? What is our power? What would it mean to win?

Almost ten years after “Seattle” this film explores the impact this movement has had on contemporary politics. Seattle has been described as the birthplace for the “movement of movements” and marked a time when resistance to capitalist globalisation emerged in industrialised nations. In many senses it has been regarded as the time when a new social subject – the multitude – entered the political landscape. Recently the counter-globalisation movement has gone through a certain malaise accentuated by the shifts in global politics in the post 911 context.

The protests in Heiligendamm seemed to re-assert the confidence, inventiveness and creativity of the counter-globalisation movement. In particular the five finger tactic – where protesters spread out across the fields of Rostock slipping around police lines – proved successful in establishing blockades in all roads into Heiligendamm. Staff working for the G8 summit were forced to enter and leave the meeting by helicopter or boat thus providing a symbolic victory to the movement.

“What Would It Mean To Win?”, as the title implies, addresses this central question for the movement. During the Seattle demonstrations “we are winning” was a popular graffiti slogan that captured the sense of euphoria that came with the birth of a new movement. Since that time however this slogan has been regarded in a much more speculative manner. This film aims to move beyond the question of whether we are “winning” or not by addressing what would it actually mean to win.

When addressing the question “what would it mean to win?” John Holloway quotes Subcomandante Marcos who once described “winning” as the ability to live an “infinite film program” where participants could re-invent themselves each day, each hour, each minute. The animated sequences take this as their starting point to explore how ideas of social agency, struggle and winning are incorporated into our imagination of politics.

Venezuela from Below

d’Oliver Ressler et Dario Azzellini (67min, 2004)

In Venezuela, a profound social transformation identified as the Bolivarian process has been underway since Hugo Chávez’s governmental takeover in 1998. It concerns a broad process of self organization, from which has developed a progressive constitution, a labor law, new educational possibilities, and a number of further reforms for the impoverished majority of the population of what is potentially a wealthy state. The government’s politics, which take an open stance against neo-liberalism, have experienced vehement rejection from Venezuela’s major private industries and from the U.S., expressed in two attempted coups and boycotts. Nonetheless, Chávez and his government enjoy the trust of the majority of the population. The society is heavily politicized; many people who had never before thought of what they wanted to change are now a part of a profound transformation taking place in the country.

In the film “Venezuela from Below,” the true actors in the social process are able to speak: the grassroots. After an introduction by philosopher Carlos Lazo, workers from the oil company PDVSA in Puerto La Cruz report how in 2002/2003 they protected the refinery from breaking down during the oil sabotage, which was pawned off as a strike, and how they were able to reinstate oil production. Several farmers from a newly founded cooperative in Aragua report on their process of self organization, on the literacy campaign, and how things should continue. A women’s bank project in Miranda and several loan recipients from Caracas’ disadvantaged district, 23 de Enero, present their projects. Indígena community members near the Orinoco river in Bolívar speak about how their demands and struggles are reflected in the constitution and what has changed for them. Workers from the occupied National Valve Company in Los Teques and the paper production company Venepal in Carabobo – which was occupied by 350 workers after the owners drove it to bankruptcy, and which now, after a partial agreement, is running production again – speak about corrupt unions, labor control, and their struggles. Protagonists in the revolutionary movement Tupamaro, the cultural foundation Simón Bolívar, the leftist website www.23.net, and the Bolivarian Circle Abrebrecha from 23 de Enero report on their work and what has changed for them through the social revolutions.

The film is available in Spanish, with English or with German subtitles.

5 Factories–Worker Control in Venezuela

d’Oliver Ressler et Dario Azzellini (81min, 2006)

In their second film regarding political and social change in Venezuela, after “Venezuela from Below” (67 min., 2004), Azzellini and Ressler focus on the industrial sector in “5 Factories–Worker Control in Venezuela“. The changes in Venezuela’s productive sphere are demonstrated with five large companies in various regions: a textile company, aluminum works, a tomato factory, a cocoa factory, and a paper factory. In all, the workers are struggling for different forms of co- or self-management supported by credits from the government. “The assembly is basically governing the company”, says Rigoberto López from the textile factory “Textileros del Táchira” in front of steaming tubs. And coning machine operator Carmen Ortiz summarizes the experience as follows: “Working collectively is much better than working for another–working for another is like being a slave to that other”.

The protagonists portrayed at the five production locations present insights into ways of alternative organizing and models of workers’ control. Mechanisms and difficulties of self-organization are explained as well as the production processes. The portrayal of machine processes could be seen as a metaphor for the dream machine of the “Bolivarian process”, and the hopes and desires it inspires among the workers. The situation in the five factories varies, but they share the common search for better models of production and life. This not only means concrete improvements for the workers. Aury Arocha, laboratory analyst at the ketchup factory “Tomates Guárico”, emphasizes that the difference between “social production companies” (EPS) and capitalist corporations is that the EPS “work for the community and society”. Carlos Lanz, president of the second largest aluminum factory in Venezuela, Alcasa, coins the key question: “How does a company push toward socialism within a capitalist framework?”

The film ends with an extended sequence from a management meeting at Alcasa, a company with 2.700 workers, with discussions about co-management and the changes of production relations they aspire towards.

The film is originally in Spanish and available with German or English subtitles.

The Fittest Survive

d’Oliver Ressler (23min, 2006)

Factors like “danger”, “risk” and “wilderness” are no longer considered only in the dark, suppressed underside of the globalisation dream. These possibly deterring factors have become a resistance to be overcome by, apparently, only the best and the strongest. Thus, to a certain extent, mastering these daunting elements have become standards for achievement in the economic discipline. The crisis regions’ growth markets make particularly clear that the law of market economics requires hardness and ruthlessness. This warlike character of market economics transforms life into a fight in which specific individuals face ever-higher demands for better performance.

In order to prepare for this competitive, social Darwinist, pecking order of global capitalism, privately-owned, security enterprises offer their self-developed, civilian training programs that simulate conflict-situations – in varying complexities up to war scenarios. One of these enterprises, the British AKE Group, promises, according to their web page, to provide “…clients the competitive advantage of engaging safely in areas that might otherwise have been closed to opportunity.”

The video “The Fittest Survive” is based on filming the five-day course “Surviving Hostile Regions” done in January 2006 in Wales, Great Britain by the AKE Group. The course instructors are British ex-special force soldiers. The participants are businessmen who are preparing for business in Iraq and other dangerous regions, government officials and mainstream journalists who, with their dishonest discourse of democracy and human rights, help to legitimise and secure the ideology of market-economics expansion.

The video, primarily filmed by hand camera, follows the survival-course participants as they experience the staged reality of live shell bombardments, an assault by armed guerrillas, the rescue of accident victims, and moving through mine fields. Above this training camp in Wales, low-flying British fighter planes hold manoeuvres and foreshadow the real war theatres in which the class participants will soon be.

The video “The Fittest Survive” is available in English and German versions.