Wednesday, December 11, 2013

For a non-linear history of Mexico

7pm – Cinema 2

Oliver Debroise / Mariana Castillo Deball / Monica Mayer

Encounter with Monica Mayer (artist, Mexico) and Annabela Tournon (art historian, EHESS).

Curated by Aliocha Imhoff & Kantuta Quiros

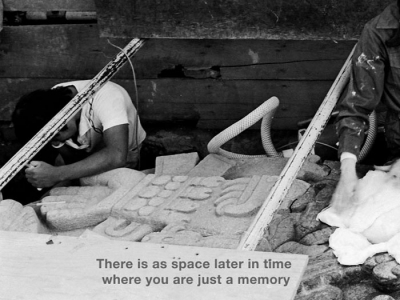

Mariana Castillo Deball, There is a space later in time where you are just a memory (2010, 7 min)

Castillo Deball’s work explores material culture and the two basic forms of narrative discourse: history and story telling. Contrasting the circular temporality of the myth with the lineal temporality of the historical discourse, the artist deconstructs official narratives in favour of a personal and fragmentary perspective, where the fracture between the subject who remembers and what is remembered is widened. This video presents two narratives, the Aztec myth of the goddess Coatlicue and her daughter the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui dismembered by the sun as a punishment, and a popular traditional story about a hunter who devours himself. Both stories remit to an action where the moment of narrating implies a refiguration in time. In contrast with these narratives, images are presented of archaeological excavations in Mexico City in the 1970s; these digs took place as a result of the chance finding of a circular stone disk representing the image of the moon goddess. Contaminated by stories of dismembering and autophagy, the nationalist discourse of history devours itself, leaving behind disperse signs of absence and shreds of meaning. Mariana Castillo Deball (Mexico City, Mexico, 1975) studied visual arts at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas and Philosophy at Universidad Iberoamericana, both in Mexico City. Completed postgraduate studies at Jan Van Eyck Academie, Maastricht, Holland. Solo exhibitions include: Amikejo: Uqbar Foundation, MUSAC-Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, León (2011); Museo Experimental El Eco, Mexico City (2011); Between you and the Image of you that reaches me, Museum of Latin American Art, CA (2010); Kaleidoscopic Eye, Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland (2009); Nobody Was Tomorrow, Barbara Wein Gallery, Berlin (2008); Estas Ruinas que ves, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City (2006). She has received the distinctions: Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Grant (2006) and Prix de Rome, first place, Amsterdam (2004). Together with Irene Kopelman she is a founding member of the Uqbar Foundation. Her work is included in the Jumex and Castello di Rivoli collections.

Mariana Castillo Deball, There is a space later in time where you are just a memory, 2010, Video still, courtesy Barbara Wien Wilma Lukatsch

Olivier Debroise, Un Banquete en Tetlapayac (1997-1998, 90 min)

Un Banquete en Tetlapayac is Debroise’s contemporary reenactment of the events surrounding the filming of director Sergei Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico (1931). Eisenstein’s production was halted for some time when the lead actor went to jail for accidentally shooting his sister. During the hiatus, the crew spent time at the Hacienda Tetlapayac, watching movies, eating, drinking, debating, and dancing. Sixty-seven years later, Debroise invited a group of artists, filmmakers, and intellectuals to reconstruct what happened at the hacienda. Un Banquete is both an homage to Eisenstein’s directorial legacy and an investigation of representation, nature, and history itself. The renowned author, art critic and curator Olivier Debroise died from a sudden heart attack in the evening of Mai 7th 2008 in Mexico City. Debroise, born in 1952 in Jerusalem and French citizen, lived in Mexico since 1970. He became one of the most influential personalities of the Mexican art scene, due to his numerous articles and publications on modern and contemporary art in Mexico, his commitment as curator and co-curator of diverse exhibitions, as well as co-organizer and participant of several symposia. His last large exhibition project, curated together with his friend and colleague Cuauhtémoc Medina, was “La era de la discrepancia. Arte y cultura visual en México, 1968-1994” (The Age of Discrepancies. Art and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1968-1994), shown in 2007 at the Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Artes (MUCA) in Mexico City. Other important exhibitions under his direction, respectively his decisive conceptual participation were: “Modernidad y modernización en el arte mexicano”, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, 1991; “The Bleeding Heart / El Corazón Sangrante”, ICA, Boston, 1991; “David Alfaro Siqueiros: Retrato de una década”, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California; Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1997. Olivier Debroise was co-initiator, and from 1993 until 1997, director of CURARE, the art critics’ and art historian’s association founded in 1991 in Mexico City, dedicated to interdisciplinary research and analysis of Mexico’s visual culture, which publishes the magazine of the same name. Since 2004, Olivier Debroise was in charge of the collections of contemporary art of the UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), building up the collection, which will be shown in the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo, once the new edifice is finished.

Monica Mayer, One More Dinner… or a Banquet in TetlapaMUAC. (2011, extraits)

Mónica Mayer is primarily a performance artist, but she is also a feminist sociologist and—together with Victor Lerma, her husband—she has kept an exhaustive archive of news articles about contemporary art. It is for this reason that she curated the exhibition Una visita al archivo Olivier Debroise: entre la ficción y el documento at the “Arkheia” Documentation Center of the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in 2011, taking into consideration the important task of reactivating Olivier Debroise’s archive. Debroise, a French citizen who lived and worked in Mexico since the age of 17, was a prolific art historian focused on Mexican art and through his research he created his own archive. Amongst the different reactivation strategies Mayer included in the exhibition was the video of a performance that seems to be nothing more than a simple dinner party amongst friends. However, on closer inspection, it proves to contain a meta-narrative related to Debroise’s own methodology of research and his passion for creating his own archive. The performance recorded in the video was titled One More Dinner… or a Banquet in TetlapaMUAC (2011), an allusion to Debroise’s own film, A Banquet in Tetlapayac (1997-1998). What we see in the video is a dinner Mayer organized with Debroise’s closest friends and collaborators. The idea was to recall personal events that involved Debroise, recognizing his role as a researcher of Mexican art. Anecdotes about his youth, his homosexuality, and his Jewish background were discussed in order to understand the development of his research methodology, personal style, and the literary discourse of his novels, which included a historiographic perspective. The dinner took place at the Hotelito San Rafael, a cozy bed-and-breakfast belonging to Miguel Legaria and Cuca Valero, who also own the adjacent apartment where Debroise lived and died. The particularity of Debroise’s archive resides in the way in which it was assembled: the accumulated material allows us to see the process by which he compiled artists’ photographs and personal documents, which he then used to artistic ends—such as in the writing of his novels and even as the raw material for A Banquet in Tetlapayac. This film refers directly to Sergei Eisenstein’s film Que viva México! (1930-1932), but flips the original on its head. Eisenstein’s film can be considered a documentary or, better yet, a “filmic archive”—Eisenstein was never able to finish editing it the way he wanted to and, therefore, we will never know what his desired final montage for the film would have been. Divided into chapters, Que viva México! was dedicated to the artists that inspired Eisenstein in his celebration of what he images as Mexican identity: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Jean Charlot, El Greco, Francisco de Goya, José Clemente Orozco, José Guadalupe Posada, and Diego Rivera. One of the locations of Que viva México! was the Tetlapayac Hacienda in Apan, a small town in the state of Hidalgo. This hacienda was one of the wealthiest during the revolutionary period but by the time Eisenstein visited its owner, Alejandro Saldívar, had seen better days. The ruined and weary Don Alejandro only came to life when he sat down to eat at the head of the dinner table: his eyes sparkled at the spectacle of food and drink. He shared these moments of pleasure with Eisenstein, dining on exotic dishes such as chiles en nogada with pecans and pomegranates, oyster soup, lobster, and escamoles (ant eggs). This anecdote, among many others, shows us what shaped Eisenstein’s view of Mexican history as something that had been interrupted, left incomplete: the ruined old cacique and the humiliated campesinos, who had no way of claiming the rights they were entitled to, were the product of a failed revolution. While Eisenstein focused on the folklore of Mexico, lending it a mythic quality—which critics consider symptomatic of European romanticism—but also trying to insert the country into a modernist discourse, Debroise in A Banquet in Tetlapayac presents an overload of constructions of the “Mexican.” For his film, Debroise invited his friends to stand in for the historical characters that visited the Tetlapayac Hacienda while Eisenstein was staying there. Some of these visitors were asked to give speeches about Eisenstein, without specific dialogue; Debroise wanted his guests to base their performances on their own interpretations of the role they were playing. One of the main sequences of the film is a dinner. Twelve people sit at a table drinking pulque and eating chiles en nogada (what else?) and other exotic Mexican foods, discussing art, communism, and revolutionary icons. It was an act of reflection, adaptation, representation, revision, and even rejection of the roles they had been asked to perform. The dinner party in the film becomes an act of writing history—once again fragmented, incoherent, and incomplete. This reenactment presents the eternal conflict of the representation of post-colonial national identity. According to the art critic Cuauhtémoc Medina, A Banquet in Tetlapayac is intentionally “a kitsch postcard of communism in Mexico,” although Debroise’s layered critical mechanisms transcend this perhaps oversimplified explanation. In her own reenactment of the banquet, Mónica Mayer and her husband both play the role of Hunter Kimbrough, Upton Sinclair’s brother-in-law. Upton Sinclair was the Hollywood producer who provided financial support for the movie until Eisenstein sent him some homoerotic drawings instead of the film. Hunter Kimbrough was the administrator of the production’s funds, but was also a spy sent by the Soviet Union to report on the work of its filmmakers. Mayer decided to take this role in her own video because she was not in fact a close friend of Debroise’s; her role was to be the “researcher of the researcher.” In this second reenactment of Eisenstein’s dinner, Mayer is, in a subtle way, the agent of historical memory; this third banquet features the same food as the first two. However, the chiles en nogada here become the signifier of a substance that all the guests have in common—they refer to the guest’s shared responsibility to preserve Olivier Debroise’s archive and to promote its relevance. In recent years, Mexico City has attracted attention as a chaotic mega-city that possesses a rich cultural history, while remaining a reasonably inexpensive place to live that is no longer provincial or even nostalgically modernist but rather pluralist and plays the role of an international platform for contemporary art and aesthetics. It is, following Mayer’s reframing of Debroise’s engagement with Eisenstein, our responsibility as viewers to become aware of the links between memory, documentation, and the present within today’s global art landscape. (Mireille Torres, Una cena mas by Monica Mayer, 2012, in e-misferica, vol 9, On the Subject of Archive. https://

Monica Mayer, One More Dinner‚ or a Banquet in TetlapaMUAC., 2011, video still, Courtesy Monica Mayer

Text: Olivier Debroise 1952 – 2008 : Shock Waves Text by Cuauhtémoc Medina

Some lives can’t fit in a single lifetime; they challenge our expectations about how many stories could possibly be provoked, contained, told and thought by a single individual. Olivier Debroise was one of the most ferocious art critics and curators in Mexico, a homosexual novelist who explored the intersections of history, violence and desire, and a cultural agent who was equally devastating in destroying myths and sustaining institutional transformations; and this is only the beginning. His death has created a massive commotion, because Debroise did not merely treat culture as his profession. He was a potent force within a multitude of critical circles that extend across disciplines, iconographic camps, academic circuits, and creative trajectories, and his loss has permanent ramifications for all those that he touched. Tempestuous, brilliant, and tireless, Olivier Debroise was a representative of an era in which fixed concepts of identity—personal, professional, and political—lost meaning, giving way to a contemporaneity in which the past is always active, and radicalism functions without need of dogmas. In a world of organic intellectuals and fossilized academics, Olivier saw the opportunity to treat culture like an adventure series within the cycle of upsets that was the twentieth century. What follows is an incredible, though incomplete, list of the roles he played, shots he fired, and crossfire in which he was caught: – A heterodox historian who beginning in the late 1970s bombarded the official narrative of Mexican modernism, exploring the cubist structure underlying Diego Rivera’s work (Diego de Montparnasse, 1979), chronicling the marginal artistic circuits of the 1920s and ’30s (Figuras en el trópico, 1982), dissecting the cadaver of the “mass individual” in Siqueiros’s painting (Portrait of a Decade, 1997), and articulating a polemical geneaology of contemporary art (Age of Discrepancies, 2007). – An anti-psychiatric activist who worked with Félix Guattari and Suely Rolnik. – The inventor of the notion of the curator as a leftist cultural politician, a critical virus of globalization, and an agent of continuous intellectual effervescence. The founder and ideologue of Curare (1991-1997), the Camara Nacional de Industrias Artísticas (National Chamber of Art Industries, CANAIA) (2001-2004), Teratoma (2000-2008), and more recently, the curator responsible for reactivating the neglected task of forming public collections of contemporary art in Mexico through his work at the MUAC (University Contemporary Art Museum) of the UNAM (National Autonomous University). – The experimental filmmaker who, having worked on Jodorowsky’s La Montaña Sagrada, absorbed the actoral improvisation of Claude Lelouch and the intellectual poetics of Godard and Pasolini, and succeeded in producing one of the most audacious feature-length experimental films ever:Un Banquete en Tetlapayac (A Banquet in Tetlapayac, 1997-1998), a re-interpretation and tableau vivant that addresses the paradoxes of Mexicanism, communism and homosexuality within Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Qué viva México! (1931-2). – The travelling companion of three or four generations of artists: from Enrique Guzmán and Javier de la Garza to Rubén Ortiz or Miguel Calderón; from Carla Rippey, Adolfo Patiño and Mario Rangel to Francis Alÿs, Silvia Gruner and Melanie Smith; from Lola Alvarez Bravo to Claudia Fernández and Miguel Ventura, etc., etc. – The axis of a series of unthinkable theoretical, geographic, and literary maps and axes: from Carlos Monsiváis and Luis Zapata to Susan-Buck Morss and Ivo Mesquita; from Sweden to Patagonia and Los Angeles; from Sovietology to Nomadism; from Tijuana/San Diego to the sixteenth-century Chichimec border wars. – Intellectual accomplist; institutional conspirator; bureaucratic saboteur; infatigable smoker and seducer. Olivier frequently insisted that though he was born in Jerusalem in 1952, it was when that city was a part of Palestine. At 17, he deserted his parents’ diplomatic circuit to settle in Mexico, which was, for him, the site of commitment and liberty. In his last moments, Olivier Debroise was accumulating new and unfinished projects. His death was sudden and unpredictable—as impulsive as Olivier himself.

Translated by Jennifer Josten.

This evening is supported by the Institut Culturel du Mexique