Nous reprenons ici l’entretien que nous avions publié sur le blog elles@centrepompidou

Née en 1934, San Francisco (Californie, États-Unis), Yvonne Rainer vit à Los Angeles (Californie, États-Unis).

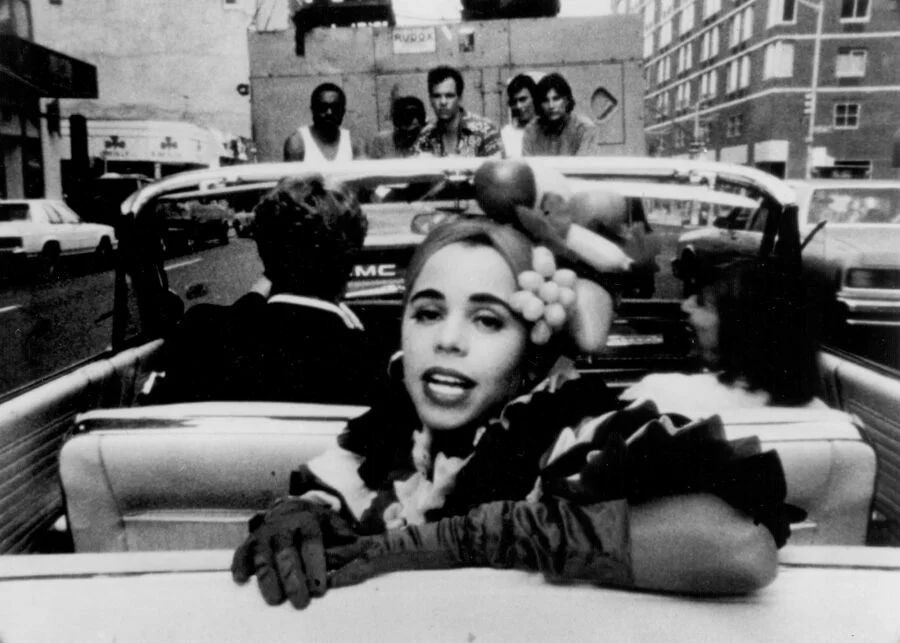

Aliocha Imhoff & Kantuta Quiros : Yvonne Rainer, nous souhaitions vous interroger à propos de la double transformation qu’a connu votre travail pionnier de chorégraphe au sein de l’avant-garde new yorkaise. Votre travail s’est en effet de plus en plus politisé, partant d’un travail chorégraphique très formaliste, jusqu’à une prise de conscience féministe dans les années 70, pour enfin donner naissance à un film comme Privilege en 1990, qui met en scène l’entrecroisement des relations entre racisme et sexisme. Or, c’est dans le même mouvement, que vous vous êtes tournée vers le cinéma vous distanciant progressivement de la danse. Comment s’est passé ce passage de la danse aux images, au cinéma ? Enfin, comment concevez-vous le lien entre art et politique dans votre travail ?

Yvonne Rainer :

In the early 70s when I made the shift from dance to film, the reasons were multiple: an aging body, a disinclination to form a dance company with all that entailed, an interest in experimental film, which I had followed from the late 50’s, and wanting to deal with narrative, with fiction and with the feminist issues that were arising, and my experience as a woman. Film, with all its possibilities for combining image, text, and voice, seemed to offer more possibilities than dance, or the kind of dance that I did, which was not narrative, but athletic and abstract. Film just seemed a much more open arena for exploration.

Some years ago someone asked me “why do you always concern yourself with exposing the conditions of production of filmmaking and do you see yourself as progressing beyond it?” This is a very political question, and I responded as though someone had thrown down a gauntlet:

”The word ‘beyond” suggested a failure you have to overcome. The question also implied that one was making films simply for antagonistic or contestational reasons. I was interested in the positive conception of formal playfulness as opposed to the negative connotations of the deconstructive position. There was, of course, a serious justification that had to do with the fluidity of signifiers and disruption of fixed social positions. If narrative structure was an analogue for social hierarchy — and there had been much theorizing about this — then the disruption or messing around with narrative coherence had a positive function in pointing toward possibilities for a more fluid and open organization of social relations. This was, of course, an ongoing project, not at all subject to aesthetic fashion, not something I attempted or intended to “get beyond,” or “cross over” from, or rise above. By the early 80’s my own relation to narrative had become increasingly complicated. I saw narrative as an effective “gripping device,” or means of engaging an audience and as such, something that had to be considered and mastered. This meant that situations and characters had to have varying degrees of credibility. It was necessary, however, that the coefficients of time and space be played with – for comic relief, for disruption, for foregrounding “the apparatus,” for allowing analysis and commentary. I was echoing Brecht and Godard, perhaps, but with regard to Brecht, I wanted more details of everyday life, and regarding Godard, I wanted more psychological truth.

For awhile I followed and was influenced by the arguments and critiques of feminist writers like Teresa de Lauretis and particularly Laura Mulvey’s famous “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” which construed mainstream cinema as a vehicle for men to overcome female obstacles to their self-discovery and attainment of manhood. These writings described the deployment of female figures in the noir and western genres as the creation of enigmas to be deciphered and controlled or threatening landscapes to be traversed and possessed. And narrative structure, with its development, climax, and dénoument, was in and of itself implicated. But subsequently I realized that there are all kinds of narratives, histories of marginalized or “disappeared” people who have not had a fair shot at being represented, and it seemed obvious that narrative structures can be used for both progressive and oppressive ends. As a consequence, it became difficult, for me at least, to sustain a political critique of narrativity. Let me just say that I was interested in creating situations for different kinds of spectator engagement within a given film. And narrative was only one of these.

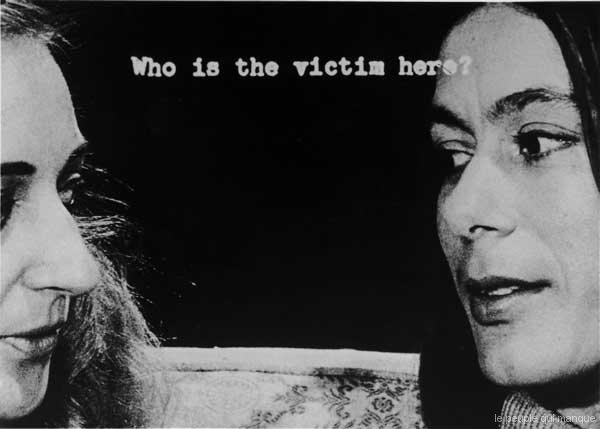

Another question arises: Why was it so important for me constantly to remind the audience — via all kinds of strategies — that these apparitions on the screen are fabrications? Around 1985 I wrote, “…words are uttered but not possessed by my performers…” When I first started using more than one performer to play a given character – in Film About a Woman Who… two women stand in for the “she” – it was more an aesthetic or formal, rather than political choice; mixing up the referents simply made things more interesting and lively. Later I would say that detaching meaning from the speaking subject was one way of forcing the spectator to deal with issues in a broader social field rather than being vicariously swept away on a tide of simulated individual experience. The visual de-centering of the subject has a philosophical and historical parallel in poststructuralist writing, like Barthe’s “Death of the Author”, Foucault’s “What Is an Author?” and Julia Kristeva’s work, which I was reading around 1980. The romantic notions of unified personhood and stable identity were under attack for the next decade. Kristeva’s “subject-in-process” was especially appealing to feminists who were struggling to get out from under the tyranny of gender masquerade. With the advent of post-colonial writing, however, the focus of discussions shifted from gender to race, and there were wonderful films made about African-American experience, particularly those of Charles Burnett and Julie Dash. The writings of Stuart Hall and Homi Baba have been influential in recasting the debates about identity in terms of cross-cultural hybridity.

This is all very superficial and sketchy, but it may provide a framework for following my particular path from formal avant-garde to experimental social narrative. Here is an afterthought: From my earliest choreography, I never thought of my chosen medium as a vehicle for “self-expression.” This was partly John Cage’s influence; somewhere in my head I hear either him or Merce Cunningham saying “If you want to express yourself, take up basket-weaving.” Which in retrospect makes little sense, given Native Am erican traditions and the cultural and social functions of basket weaving. But at the time I interpreted it to mean that of all the things in the world available to the artist, the self, or its integrity, is only one inconsequential element. Of course, in terms of Cage’s practice, disposing of self-expression was key to the elimination of personal choice in art-making via aleatory methods of composition, and was even perhaps an indirect influence on subsequent notions of gender mutability.

I use the past tense in the above paragraphs because I have not made a feature length film since 1996 (MURDER and murder), when I began to drift back in to choreography. If I do re-enter the film arena, I’m not sure what my modus operandi will be.

Yvonne Rainer

1990-2008

Entretien inédit réalisé en juin 2008 par Kantuta Quirós & Aliocha Imhoff / le peuple qui manque